The idea of using the rhizome (originally a botanical description for structures like ginger roots) as a philosophical concept was first posited by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in their book A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (London: Athlone Press, 1988). The rhizome concept suggests a way of structuring knowledge (and learning) that is non-hierarchical, imminent (in the process of endlessly becoming), rootless…(as compared to logical, static, closed, hierarchical).

Dave Cormier, a significant voice in translating these ideas to the present (and specifically to the information age) and to the learning process, has blogged and published on the focused concept of Rhizomatic Learning. Starting from the concept “You don’t know what you don’t know“, Cormier looks at how the rhizome metaphor is useful to address this learning problem that is particularly apparent in the present day. Rhizome qualities show us a useful approach to “learning for uncertainty”. The rhizome is a particular kind of network, which is collaborative, creative, untidy, with no real start or end, adapting to the ecosystem around them. Here is Dave Cormier giving a very useful video introduction to Rhizomatic learning, appropriately entitled Embracing Uncertainty:

While exploring (in good rhizomatic fashion) the theme of rhizomatic learning and museums that exist entirely in the virtual space, or which use digital means to reach out to audiences who can’t physically visit, I found a marvellous site: Girl Museum . Girl Museum is “Girl Museum is the first and only museum in the world dedicated to celebrating girlhood” It is entirely virtual. They describe their role in their Impact statement:

“providing a safe virtual space for education and discussion of girl culture in the past and present. We also manage social media channels and other projects dedicated to advancing girls’ rights today, sharing stories that celebrate girls and their contributions, and empower girls to become active in documenting, preserving, and sharing their history and culture”

This is a truly fantastic site. I jumped into a number of their virtual exhibitions, starting with this one, called 52 objects. Created progressively, week by week, in 2017, the exhibition was curated on the idea that “many “history of the world” programs routinely left out the stories of young girls, we scoured the globe for objects that would bring to light girls’ daily lives, struggles, and heroism.” They used a variety of digital means to share the content, including a google map showing where various objects originated from:

You can then link to individual items in the exhibition, such as this one:

So where does this all fit into the rhizomatic question? The creators/content generators of Girl Museum directly associate rhizomatic ways of thinking and learning with their site, and its mission, writing about this in an article, BECOMING-GIRL-MUSEUM published in 2011 in a journal aptly titled Rhizomes.

They write how Girl Museum, and its digital and every-expanding exhibitions work: ‘Projected out into a pixel-based world are the powerful stories of us all—past, present, and future—necessary to share and understand, growing rhizomatically, constantly creating newness and variation through inter(net)connectivity. We resist the conventional, striving to (re)define ‘girlhood’, while simultaneously unfixing ‘girl’. We are (Becoming-) Girl Museum.”

The exhibition Across Time & Space, is an example of the way the digital exhibitions can rewrite versions of ‘girlhood’, taking concrete objects or documents from the past and recontextualising them in the digital ever-present, and through new juxtapositions, they challenge the way we think about them – and about girl/womanhood. Historical, cultural and social interpretations are constantly being layered over cultural artefacts, and the digital exhibitions allow us to ask when, where and how these versions of female experience were defined and modified. In these online exhibitions, co-curated and co-created by many girls and women, “Girls (and Becoming-girls) can create and contribute content based on their views and experiences, and interact with the content created by the views and experiences of other girls. With each new submission [the virtual exhibition] grows and changes to reflect the inspirations of its contributors.” The virtual museum disrupts the traditional art historical or anthropological meaning of objects, ‘nomadically’ and iteratively opening new spaces for interpretation. This is where the rhizomatic analogy allows us to see the structure and its value. And because it happens in the virtual space, it is relatively unconstrained in the process, particularly in comparison to what a physical version of this might look like in a traditional museum. The authors note:

“Traditionally, museums are collections of objects, concepts, definitions, people, and thoughts. Virtual museums, by their very nature, are composed of all these elements, but can be pulled from universal experience and not linked to any single or specific collection. Though they can be hindered by a lack of physical resources, this can also be advantageous because virtual museums do not have to be static. The virtual assemblages of objects, concepts, and definitions can feed off each other, generating new concepts, more definitions, new ideas, and, as many museums move toward a more interactive experience, new objects” http://www.rhizomes.net/issue22/museum/index.html

As Remer, Wiedmann et al note about the collaborative, unhierarchical and rhizomatic approach to exhibition creation, “In this way the goal of collecting multiple, diverse viewpoints from girls on what constitutes a heroine, is fulfilled on a global, easily accessible platform“.

It substantiates what Dave Cormier has formulated about rhizomatic processes in the form of collaborative knowledge construction. Cormier writes: “Collaborative knowledge construction is also being taken up in fields that are more traditionally coded as learning environments. In particular, social learning practices are allowing for a more discursive rhizomatic approach to knowledge discovery. Social learning is the practice of working in groups, not only to explore an established canon but also to negotiate what qualifies as knowledge.” In the Girl Museum, participants use the virtual space to challenge the canonic ways girlhood has been defined through material culture, and are simultaneously exposed to a hugely diverse range of objects and artefacts, that will provoke further explorations.

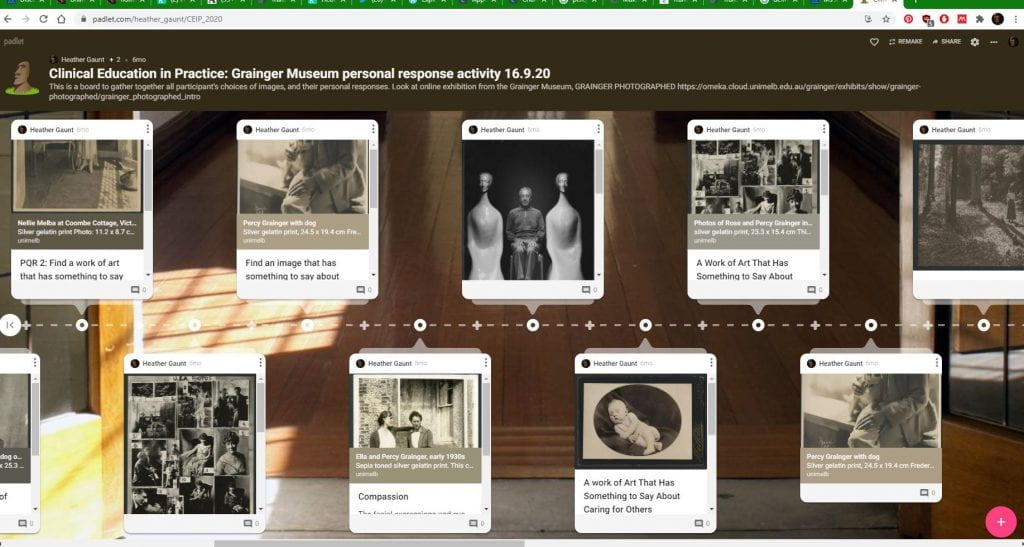

All this has great resonance for me, personally and professionally. My curatorial approach in recent years when I’m working in the university museum space (such as in the exhibitions Multivocal and How it Plays) has been to seek continuously open conversations and follow (human) leads to shape and fill the content for an exhibition and its associated educational engagements. This might be in the form of professional collaborations, student-commissioned elements, and inclusion of student-generated creative content that responds to the exhibition, in the content of the exhibition itself.

To conclude, I think what we’ve been able to achieve (as a collaboration between Museums & Collections staff, UoM academics, and UoM students) in these online creative and pedagogical engagements by students in 2020 with the exhibition Multivocal, can actually be understood as illustrating the idea of rhizomatic learning: open ended, non-hierarchical, shared…

REFERENCES

Cormier, D. 2008. Rhizomatic education : Community as curriculum. Innovate 4 (5). Reposted in http://davecormier.com/edblog/2008/06/03/rhizomatic-education-community-as-curriculum/

Remer, Ashley E. , Kathleen Weidmann, Lara Band, Briar Barry, Miriam Musco, Julie Anne Young. 2011. BECOMING-GIRL-MUSEUM, Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge. 22. http://www.rhizomes.net/issue22/museum/index.html#_ftn23