“The meaning and functional role of museum artifacts does not

Henrikka Vartiainen, Principles for Design -Oriented Pedagogy for Learning from and with Museum Objects, 2014

depend solely on the affordances of the museum or the properties of the artifacts, but is mediated by context-bound interactions of the subjects, their intentions, and tools.”

I often reflect on our opportunities to be continually more creative and collaborative at the intersection of University museums and academia. It is such a fertile space, largely because of the aligned of the ‘core missions of both museums and universities as collaborative spaces for dialogue and learning‘.(Speight et al, p. 3) We need to be pushing boundaries that we often don’t even realise are there, for the purpose of evolving new kinds of spaces, both physical and virtual, to promote more effective and transformational learning and engagement, and opportunities for creative graduate research translation.

“..when moving beyond the traditional model of educators and students in classrooms to a learning model that brings together students, museums, and expert communities, the new forms of collaboration and practices for sharing expertise present a very complex challenge. One can argue that most of the experts in different organizations have no experience of this kind of pedagogical approach that lie outside of their area of expertise. Thus, it requires extensive investigations of how diverse experts become part of the learning system, and how a reciprocal relationship for learning may be facilitated”. (Henrikka Vartiainen, Principles for Design -Oriented Pedagogy for Learning from and with Museum Objects, 2014, p. 60)

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the learning system that is the university-based museum, and what Vartianinen has accurately described as the need for extensive investigation of the system. Last year, 2020, I wrote a Strategy (laid out in Prezi) for the Grainger Museum at the University of Melbourne for the coming 5 years, which seeks to stimulate a radically engaged approach to the museum’s relationship with its academic community. (BTW, the Prezi was a highly effective virtual tool for communicating the themes and contexts of the Strategy to team members and senior University staff in the virtual world we all occupied through 2020). (BTBTW Word Press won’t embed Prezi unfortunately!)

In the Activities for the Strategy, I proposed a 3-year research project, The Grainger Lab, to measure and iteratively report on the effectiveness of the Grainger Museum’s activities to fully integrating the Grainger Museum into the Teaching, Learning and Research agendas of the University. Being introduced to the theory of Design Based Research (DBR) in this #EDUC90970 course was so timely, as it gave me a theoretical structure for thinking about how this SoTL and SoTEL project could be effectively conducted, and – just as importantly – how I could communicate the concept to Museums & Collections senior management. While this research strategy is ‘on pause’ for the moment, it helped me to think about what research translation might look like in this context.

In March this year, after learning more about DBR, I worked with UoM museum professionals and academic colleagues to shape up this Prezi presentation which we shared with the Science Gallery International Research Committee. We proposed a future Design-Based pedagogical research situated in the new Science Gallery Melbourne, and potentially travelling to other Science Gallery sites such as in Dublin. I hope that we will start this project in 2022, taking DBR as an approach to explore some of the challenges posed by Vartiainen, above.

Exploring DBR specific to museum pedagogy on the net this week as part of #EDUC90970, I came across a very interesting dissertation by Henrikka Vartiainen, which documented a multi-year education study in a Finnish forest museum. Vartianinen’s definition of the aims of DBR in her context is: “to synthesize theoretical perspectives and empirical research in order to propose an approach to participatory learning that leverages the opportunities afforded by new technology, cultural environments, and communities, especially museums”

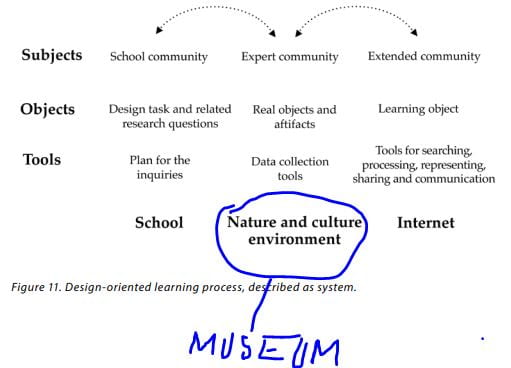

Vartiainen created a design-oriented learning environment, and tested it on school students, trainee teachers, and professional teachers. Over a number of iterations, Vartiainen believed that the research team achieved their goal, “a dynamic activity system, where a community of learners negotiates common goals, divides their duties, and focuses their object-oriented and tool-mediated activities to accomplish the multifaceted learning task …. The learning community consisted of a student, fellow students, and teachers, working with domain experts and other adults. New technology, especially social media and mobile technologies, provided tools for collaboration, and data collection, and helped to transform ideas into digital representations that could be jointly negotiated, developed, and shared with a wider community.”(Vartiainen p.44)

Design underpins both the pedagogically-driven activities (design-orientated learning), and the ongoing assessment of the effectiveness of those activities (the DBR part). Vartiainen situates DBR in the context of new museum pedagogy which privileges on ‘object-oriented actions’, rather than the old-school pedagogy of ‘the transmission of artifact-related knowledge’ (48). In this productive and participatory learning model, in which there are multiple participants in the production of meaning, “the meaning and functional role of museum artifacts does not depend solely on the affordances of the museum or the properties of the artifacts, but is mediated by context-bound interactions of the subjects, their intentions, and tools.” (Vartiainen p.48). With technological tools, students create transmissable and shareable responses to their interactions with objects, which can even become further Learning Objects alongside the original artefacts.

The practical outcomes of this multi-year pedagogical experiment is an active website for the Forest Museum and its surrounding natural environment, on which the Learning Objects are gathered and shared with other students, teachers, and the general public. The site is multidimensional, taking advantage of video, twitter feeds, maps, among many other forms. To me it feels like a nice cross between informative and overtly experimental in itself. (Some of the links don’t work, the ‘professional’ quality of some of the media varies, but I was curious and stimulated to investigate…and learn. So, I’d say successful on a lot of fronts):

https://www.openmetsa.fi/wiki/index.php/OpenForest_portal

What I found particularly exciting about Vartiainen’s dissertation was the rigorous theoretical underpinning, which situated the learning activities and outcomes in the museum in theoretical frameworks such as sociocultural contexts, and technologically mediated learning, with the overarching exploration of Design-Orientated Pedagogy. Reading this paper also compelled me to explore the concept of Learning Objects, which I hadn’t consciously encountered before. These are: “…any entity, digital or non-digital, which can be used, re-used or referenced during technology supported learning.” (As a professional who operates in a field defined in recent years as ‘Object-based learning’, I am always fascinated by the slipperiness of language around objects/artefacts… stretching from the material and into the digital. Vartiainen doesn’t disappoint in this area, exploring this complexity at length.

full meaning in relation to each other.”

A core focus of the dissertion (and of immediate interest to me in the context of #EDUC90970) is the use of technology as “a medium for enhancing design-oriented learning from and with museum artifacts”. Vartiainen observes how learners now have access to a great range of digital representations of museum artefacts, supported by contextual and tailored information via the internet. In particular, images are now cheap and abundant thanks to digital means (compared to when we used to buy art books that had 10 colour plates of highlight paintings, another 50 black and white images, and the rest text… or compared further back to when only rich folks could buy prints etched and created by Old Master printmakers such as Schongauer and Durer in the 15th century)..

Vartiainen states:

Multimodal digital artefacts may be represented in various forms or employ a combination of them, such as texts, drawings, diagrams, still photographs, multimedia presentations, animations, simulations and models of dynamic processes, interactive diagrams, maps, concept maps, databases, graphs, tables, hyperlinked web pages, audio and video files, and mathematical representations…the new technological opportunities challenge us to reconsider the current function and representation of museums in order for them to be a meaningful place for learning. Problems remain because museums seem to concentrate only on building a digital copy of the physical museum, instead of enhancing and deepening learning from museum artifacts …. To meet these challenges, this study attempts to apply the concept of the learning object to augment the meditational potential of museum artifacts.” [my highlight] (Vartiainen p. 19)

The focus for one of the design iterations, undertaken with trainee teachers, was the construction of Learning Objects for future learning activities, from physical museum artefacts. (p. 39) The design task (creating the Learning Object) orientated the interactions between subjects (students) artefacts (museum material culture) and (digital) tools, and “allowed the students to self-define and negotiate their areas and objects of interest, supported and extended by museum experts”.(p.42) The student teachers used tools such as digital cameras to shape and communicate new perspectives on the cultural artefacts, and social media platforms such as wikis as a platform for collaboration and sharing their newly created learning objects in their community of practice. Regarding the use of digital tools in the DOP, Vartiainen found in their study that “The analysis of tool-mediated activities indicated that use of participant-led photography strengthened and expanded the mediational potential of an artifact, and provided students the ability to reshape, represent, and embed the physical objects in relation to their own interest”. (p. 42)

To me, this supports an idea of a deeper and more transformative engagement by the participants with the museum environment and artefacts, beyond what we can usually achieve through talking and discussion only, in the physical space.

REFERENCES

Speight, Catherine, Anne Boddington and Jos Boys (2013). “Policy, pedagogies and possibilities”, in Museums and Higher Education Working Together : Challenges and Opportunities, edited by Anne Boddington, Taylor & Francis Group. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=4513348

Vartiainen, Henriikka (2014). Principles for Design -Oriented Pedagogy for Learning from and with Museum Objects. Publications of the University of Eastern Finland Dissertations in Education, Humanities, and Theology No 60, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu.